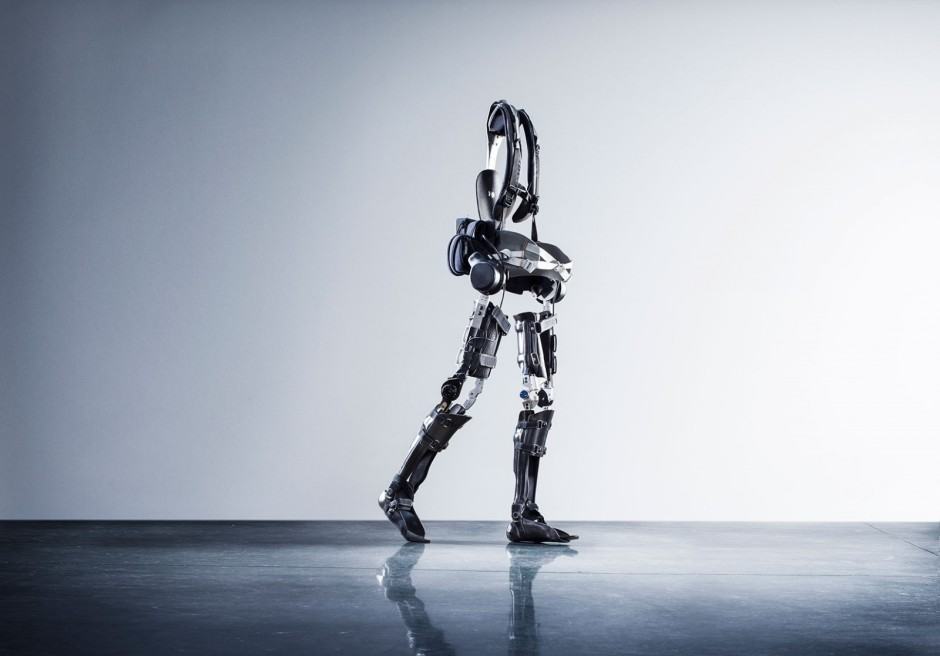

An exoskeleton named Phoenix removes cost as a barrier to walking

Steve Sanchez says the Phoenix is a breakthrough in exoskeleton comfort. “This is the first suit I’ve tried where I don’t feel like I am riding a robot,” he said. Photo: SuitX

Dr. Homayoon Kazerooni has created bionic machinery that can help a person rise out of a wheelchair and walk. Yet, there’s one barrier preventing some people from walking – cost.

This week, Kazerooni’s work takes an important step forward. His company, SuitX debuted a lightweight exoskeleton, dubbed Phoenix, for people with mobility disorders at an initial price of $40,000, about two to four times cheaper than other devices.

SuitX is also a finalist in the prestigious Robotics for Good competition and will learn this week whether it will win the top prize and funding for a pediatric exoskeleton to help children with neurological disorders walk.

“The most important thing we can do is make a device accessible and affordable,” Kazerooni, a UC-Berkley roboticist and mechanical engineering professor, told Cult of Mac. “There should be no boundaries. Walking is a basic human right.”

Exoskeletons are wearable robots, equipped with sensors and motors on an outer framework to assist in movement. The technology has shown great promise in medical applications, but devices often cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The Phoenix achieves a number of firsts in exoskeletons designed to help people walk. It’s the lightest on the market, Kazerooni said, at 27 pounds. It’s also a device the user can strap on themselves, modular pieces that can be attached to the outside of their clothes and from the person’s own chair. Many exoskeletons are bulky and require a person to transfer to a special chair to be fitted.

The Phoenix weighs just 27 pounds. Photo: Suit X

Phoenix can be fastened in as little as 10 minutes, says its main “test pilot,” Steve Sanchez, who became a paraplegic after a BMX bike accident in 2004. With a set of dedicated crutches, the user can press a button to stand and then press it continuously to walk.

To bring costs down, SuitX did away with several motors and sensors normally used on exoskeletons. Other than motors in the hips, the rest of the device was designed to work more intuitively with a person’s gait.

Costs are further reduced because Phoenix does not have to make exoskeletons in several sizes. Each modular piece is adjustable, plus the suit can be tailored to a person. A stroke victim who may have paralysis on one side may only have to wear pieces on the immobile leg.

Kazerooni wants the costs to still go lower but knows now that the price is reaching a point where the device could be covered by insurance.

“This is the first suit I’ve tried where I don’t feel like I am riding a robot,” Sanchez said. “Phoenix allows for more natural motions. It feels so much more comfortable.”

Data from the Phoenix is recorded during wearing and sent to an app on an Android tablet that is shared with a doctor or physical therapist (an iOS app is in development). The information can be used to fine-tune the exoskeleton.

Test pilot Sanchez takes in the sites of Rome before a conference. Photo: SuitX

Being able to walk is not the main benefit, Sanchez said. Phoenix allows him to get out of his chair for extended periods to get blood flowing through the lower half of his body. The prolonged sitting can cause sores that can only heal from long periods in bed, Sanchez said.

The benefit for children with neurological disorders, like cerebral palsy, is if they can learn to walk at a young age, before their muscles become too tight, it could help them have greater mobility as they grow.

For Sanchez, the benefits are more spiritual.

The wheelchair is a barrier for people who are unsure how to get close to him, Sanchez said. In Phoenix, he can be with people at eye-level and hug them without them feeling like they are embracing metal.

“But if I can see a little kid walk in this,” Sanchez said. “I will really be in my glory.”